Sunday August 17: Skardu – Gilgit

Today really is all about the seven hour drive, and in particular, the four hour drive down the Indus gorge.

The first 30km

west out of Skardu is out past the turn-off to Satpara Lake and is along a

metalled road, and by the side of the wide slow-flowing Indus. On the way we

passed some apricots drying on a wall by the side of the road. Apricot growing

is big in this part of Pakistan, and as a result, so is the drying of them.

Apparently, the ones dried in the open air are essentially fed to cattle in the

winter, but those for human consumption are dried in ovens (whatever ‘ovens’

means). Nothing of the apricot is wasted – inside the stone there is a nut –

Eidjan’s wife had threaded some onto a string and he shared them with us – very

tasty too.

The first 30km

west out of Skardu is out past the turn-off to Satpara Lake and is along a

metalled road, and by the side of the wide slow-flowing Indus. On the way we

passed some apricots drying on a wall by the side of the road. Apricot growing

is big in this part of Pakistan, and as a result, so is the drying of them.

Apparently, the ones dried in the open air are essentially fed to cattle in the

winter, but those for human consumption are dried in ovens (whatever ‘ovens’

means). Nothing of the apricot is wasted – inside the stone there is a nut –

Eidjan’s wife had threaded some onto a string and he shared them with us – very

tasty too.

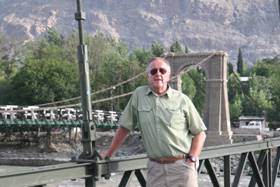

Then, just before the gorge starts the road makes a right-angle turn over a planked suspension bridge, indeed, a chap as on it repairing/replacing some of the planks as we crossed over it!

Then suddenly you

enter the Indus gorge. It is impossible to adequately describe how

awe-inspiring and spectacular this road/track is; is difficult to think of any

130km drive anywhere in the world that beats it. For the wholly of that

distance the Indus thunders through rapids. There are no pools where the river

can rest while it builds up its energy for more rapids, no, it is big raging

rapids all the way. Apparently the odd fool has tried to canoe it but no one

had got more than thirteen kilometres. In 2006 a bus with over 50 people on

board misjudged a bend and fell into the river; despite knowing where the bus

went in, no remains of the bus nor of any bodies were ever found. Such is the

power if the river. Unfortunately, photographs do not do justice either to the

majesty of the gorge or the tormented nature of the river with its constant

knots of swirling water. At various points the road crosses the river by a

suspension bridge, at other points wires are strung across the river and the

locals cross in a wooden trolley, literally pulling themselves across;

seriously hair-raising. Where there are villages there are small suspension

bridges, many sponsored by the EU to replace the hand-pulled jobs.

Then suddenly you

enter the Indus gorge. It is impossible to adequately describe how

awe-inspiring and spectacular this road/track is; is difficult to think of any

130km drive anywhere in the world that beats it. For the wholly of that

distance the Indus thunders through rapids. There are no pools where the river

can rest while it builds up its energy for more rapids, no, it is big raging

rapids all the way. Apparently the odd fool has tried to canoe it but no one

had got more than thirteen kilometres. In 2006 a bus with over 50 people on

board misjudged a bend and fell into the river; despite knowing where the bus

went in, no remains of the bus nor of any bodies were ever found. Such is the

power if the river. Unfortunately, photographs do not do justice either to the

majesty of the gorge or the tormented nature of the river with its constant

knots of swirling water. At various points the road crosses the river by a

suspension bridge, at other points wires are strung across the river and the

locals cross in a wooden trolley, literally pulling themselves across;

seriously hair-raising. Where there are villages there are small suspension

bridges, many sponsored by the EU to replace the hand-pulled jobs.

At one point,

across the river were a series of caves where the quartz veins had been mined;

you just could not see either how the miners had gotten across the river, nor

having done so, how they got up to the mines. Wherever there was a side stream

and an area of flattish land there were irrigated crops and habitation - maybe

just a couple of houses miles from anywhere, or perhaps a small village. The

road itself varies from metalled (rare, except thought small towns such as

Dasu) to track to landslip debris. It is invariably ‘single track without

passing places’, but pass you do. Despite being a virtual constant series of

bends, very occasionally you see a sign saying “BEND” – weird!

At one point,

across the river were a series of caves where the quartz veins had been mined;

you just could not see either how the miners had gotten across the river, nor

having done so, how they got up to the mines. Wherever there was a side stream

and an area of flattish land there were irrigated crops and habitation - maybe

just a couple of houses miles from anywhere, or perhaps a small village. The

road itself varies from metalled (rare, except thought small towns such as

Dasu) to track to landslip debris. It is invariably ‘single track without

passing places’, but pass you do. Despite being a virtual constant series of

bends, very occasionally you see a sign saying “BEND” – weird!

We had a late lunch at Dasu which seemed to be a friendly little town strung out along the road. Not much to report except an interesting cobbler who, although he did have a small shop, seemed to prefer to do his work on the side of the road.

Just as the gorge section starts with a planked suspension bridge, so it ends with one too. Then suddenly, around Gilgit, we are on an area of river gravels, hundreds of feet thick. It is here that the three highest mountain ranges in the world –Himalaya, Karakoram and Hindu Kush meet, and there is a monument to recognise the fact. Unfortunately it was raining when we were there – we could see the monument, but not appreciate the mountains at the same time.

At Gilgit (as in several other places) we stayed at the PTDC Hotel (Pakistan Tourist Development Corporation), which was just up from the river, which at this point is the Gilgit river and which joins the Indus itself just East of town where the Indus turns South having had to flow essentially E-W to get round the Nanga Parbit massif. . Ehsan and his family, who as noted earlier, are Ismailis and live in Gilgit (as does Eidjan) and so they went home for the night.

After depositing

our bags in our room we went for a walk down to the river. Though everything

seems calm and friendly now, there is a very considerable army presence because

in 2006 there was severe Sunni – Shia conflict and many people were killed.

Gilgit and the area around (and especially, the Hunza valley) are principally

Shia and Ismaili areas, but there are significant Sunni minorities,

particularly in Gilgit town. Gilgit is a major (all right, the only) crossing

point of the Indus and Gilgit rivers for traffic heading North up the KKH. As a

result, there are three suspension bridges over the rivers, two of which are in

town and are closely guarded by police and army. The bridges are the usual

affairs with wooden planks for the road surface, and are only wide enough for

one vehicle at a time, plus pedestrians if both are careful! However, only one

bridge is suitable for lorries and buses, and during that night, a Chinese

lorry crashed into the heavy vehicle bridge and destroyed it, though it was

never quite clear to us exactly what the term ‘destroyed’ meant. What it

did mean though was that no heavy vehicles could get north of Gilgit,

ie. up the Northern KKH and into/out of China. This was clearly going to have a

major effect on the economy of the area, and it was going to take months before

it would be fixed/rebuilt. It goes to show just how precarious life and economy

are in these remote areas.

After depositing

our bags in our room we went for a walk down to the river. Though everything

seems calm and friendly now, there is a very considerable army presence because

in 2006 there was severe Sunni – Shia conflict and many people were killed.

Gilgit and the area around (and especially, the Hunza valley) are principally

Shia and Ismaili areas, but there are significant Sunni minorities,

particularly in Gilgit town. Gilgit is a major (all right, the only) crossing

point of the Indus and Gilgit rivers for traffic heading North up the KKH. As a

result, there are three suspension bridges over the rivers, two of which are in

town and are closely guarded by police and army. The bridges are the usual

affairs with wooden planks for the road surface, and are only wide enough for

one vehicle at a time, plus pedestrians if both are careful! However, only one

bridge is suitable for lorries and buses, and during that night, a Chinese

lorry crashed into the heavy vehicle bridge and destroyed it, though it was

never quite clear to us exactly what the term ‘destroyed’ meant. What it

did mean though was that no heavy vehicles could get north of Gilgit,

ie. up the Northern KKH and into/out of China. This was clearly going to have a

major effect on the economy of the area, and it was going to take months before

it would be fixed/rebuilt. It goes to show just how precarious life and economy

are in these remote areas.